Tomorrow’s Ancestors

Cereus Art turned a Harlem apartment into a creative community lab.

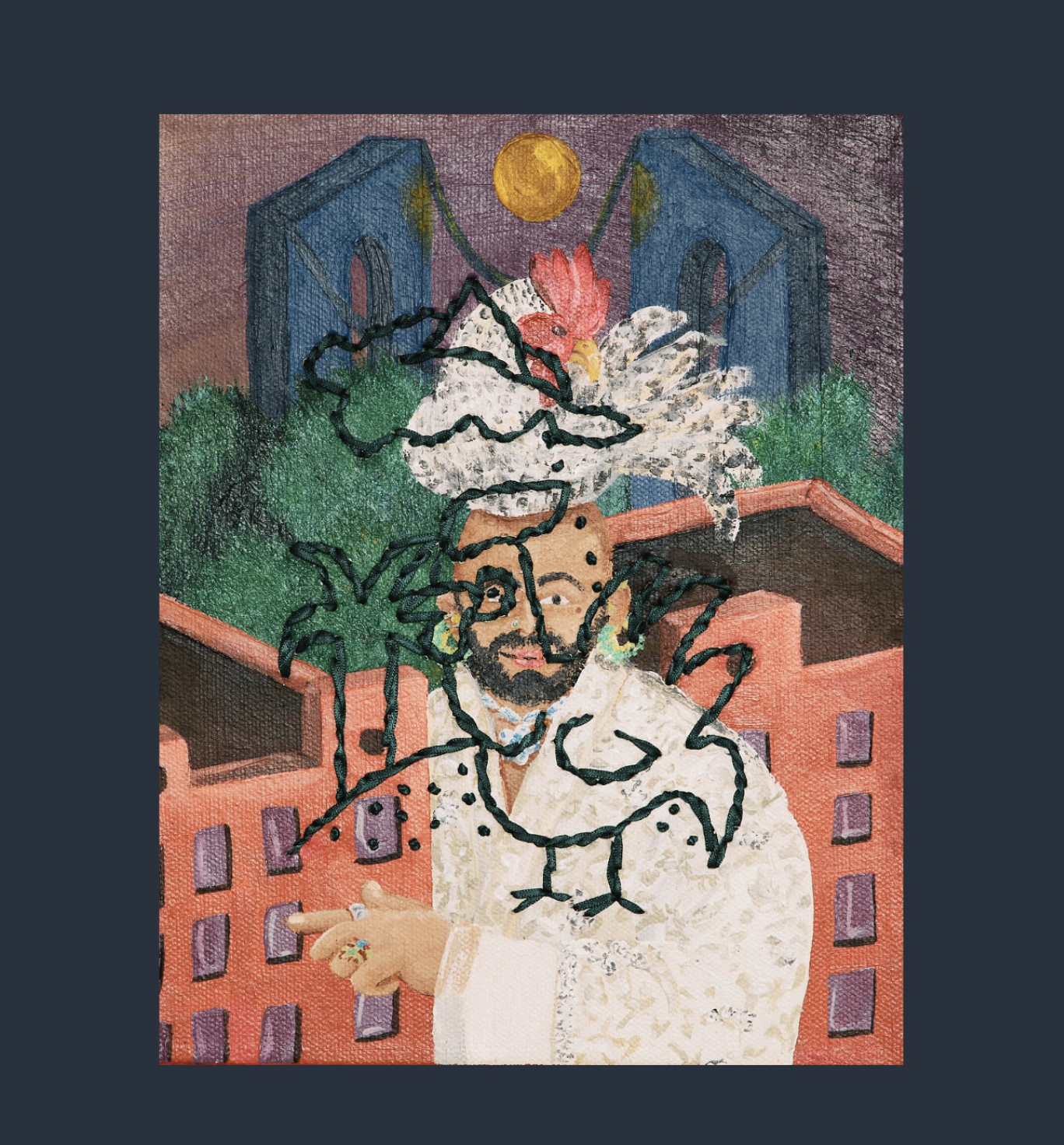

“Ya Se Nos Secaron Las Vacas” by Devin Osorio

At the heart of Tomorrow’s Ancestors is Devin Osorio—a tender, mythic, fiercely self-knowing artist whose work reads like a love letter to memory, community, and becoming. Their shrine-like paintings, immersive film, and ritual-infused installations transformed a modest Harlem apartment into something more than a gallery: a sanctuary of interdependence, reflection, and collective reimagining.

Co-created with curator and community organizer Emma Nuzzo and Cereus Art, Tomorrow’s Ancestors unfolded across June 2025 as both a solo exhibition and a vibrant constellation of free public programming. Accessibility was not an afterthought but a foundational principle. From drag shows to dye workshops, breathwork sessions to writing circles, each gathering invited neighbors not just to witness art, but to be changed by it—and to change it in return.

Even the space itself tells a story of care. Osorio and Nuzzo secured the apartment through an offering of support from a fellow creative—an act of care grounded in community-based exchange, which flowed directly into the work they would go on to cultivate. It was, in form and function, a living example of artistic interdependence.

“We found it imperative to use art as a way to bring people together with Devin,” Nuzzo writes. “Not to raise them above or separate from viewers, but to be amongst.”

This refusal to separate artist from audience, object from encounter, sits at the core of the project. Rooted in Dominican diasporic memory and queer futurist vision, Tomorrow’s Ancestors posed a quiet, radical question: What if the future is made not in monuments or museums, but in the everyday acts of care we extend to each other now? What if legacy is not institutional, but interpersonal?

“Contra Vientos Y Marea” by Devin Osorio

Reframing Home, Reimagining Art

Set inside a residential apartment uptown, Tomorrow’s Ancestors asked a deceptively simple question: What happens when we let art live where we live? Rather than elevating the artist as a distant genius or positioning the audience as a passive observer, Osorio and Nuzzo welcomed guests into a space that felt familial, porous, and alive.

“We saw the exhibition as a living, breathing piece of art itself,” they write.

Visitors weren’t merely viewers; they became participants. The back room slowly transformed over time, accumulating relics of shared experience: scribbled poems, workshop drawings, incense ash, fragments of conversations, the scent of citrus or soup lingering in the air. These weren’t residues—they were evidence of something deeply lived.

Even the programming calendar read like an art object. It was a kind of community syllabus, or what Nuzzo called a “creative lab,” spanning more than a dozen free events: a sancocho-making session with painter Kenny Rivero; a Spanglish spoken word night hosted by poet Yaissa Jiménez, complete with flash tattoos; a lecture on queer memory and urban erasure by Eddy Almonte; and a drag show hosted by Janae SaisQuoi. This wasn’t an exhibition that invited you to look. It invited you to arrive.

The night I attended began with a walkthrough led by Osorio and Nuzzo—an invitation, really. Rather than performing expertise, they spoke with warmth and clarity, weaving their vision into the room with quiet conviction. Then, without transition or spectacle, we shifted into a breathwork and journaling workshop led by healing artist Valery Mora. A dozen or so people—many of them strangers—sat in a soft circle as we were guided through meditation and breathing exercises.

Then we wrote. What struck me most was how safe it all felt. More than half the group were unfamiliar faces, and yet people shared stories of grief and transformation with astonishing vulnerability. There was no separation between the sacred and the casual, no need to announce when one part ended and the next began. It all flowed—held by intention, shaped by care.

This collapsing of hierarchies—between artist and audience, curator and participant—is not just aesthetic; it’s political. As Osorio and Nuzzo explain, the intention was to activate the liberatory potential that lives inside everyone.

As someone who’s moved through traditional art spaces, I know how frighteningly easy it is to get swept into the fine art world’s currents of elitism and narcissism. Tomorrow’s Ancestors offered something far more honest: a return to intimacy, interdependence, and the quiet radicalism of shared presence.

“Art isn’t just a specialized skill or commodity… it blossoms from the creativity which is the most innate aspect of humanity,” they write. “You ask any kid if they’re an artist and they will say YES—until about 3rd or 4th grade, when they learn their expression isn’t ‘good’ enough. We want people to unlearn this.”

This philosophy echoes the legacy of Joseph Beuys, whose concept of social sculpture imagined society itself as a work of art shaped collectively through care, imagination, and participation. Nuzzo, deeply influenced by Beuys and bell hooks alike, frames Tomorrow’s Ancestors as a refusal of art’s institutional enclosures—and a reorientation toward its anthropological roots: “a technology of connection.”

In that Harlem apartment, art became an invitation. Participation became praxis. And home was no longer a place, but a shared possibility.

“Lo Que Fue, Lo Que Ha Sido, Lo Que Podría Ser, Lo Que Pudo Haber Sido 2” by Devin Osorio

The Sacred Work of Softness

Across every touchpoint, Tomorrow’s Ancestors models what Osorio calls “a life without secrets.” Their decision to depict themselves—and only themselves—in their work is not about ego, but about ethics, clarity, and consent. “I have the right to reveal my story,” they say, “but not someone else’s.” This commitment to visibility without exploitation was born at sixteen, when Osorio came out as gay. That choice to live truthfully was catalyzed by an older man who tried to shame them for being too open, too seen. “He made me realize I had to do whatever it took to be anything other than him,” Osorio recalls. “So I made a promise to live without secrets.”

That oath now pulses through every brushstroke. Their altar-like paintings and mixed-media works fold autobiography into ancestral ritual, weaving together queer resilience, Dominican mysticism, and diasporic memory. Rooted in the teachings of Los Misterios, Osorio’s visual language conjures the intimate grandeur of sacred space: rum, feathers, mirrors, candy, plants, golden tears, painted moles, and gem-stoned nails.

Their work is also deeply shaped by queerness, not as identity, but as a spatial and spiritual practice. “As a child, I loved being encased,” they share. “Whether lying in a snowbank I had hollowed out myself or buried beneath warm laundry on the couch… that was the beginning of queer futurism for me—crafting inner universes to survive the one outside.”

In their paintings, interiors collapse into exteriors, human bodies become altars, and fixed identities dissolve into plants, animals, and objects. Gender, like space, is fluid and boundaryless. Their work expands—rather than defines—the canvas.

Nuzzo, too, speaks to the exhibition’s gendered terrain—not as binary, but as an invitation. “Gender actually wasn’t a part of it at all,” she says. “We wanted the space to feel completely boundaryless in that regard. And what emerged was something distinctly femme—not by design, but because that’s what naturally arose in a space where we prioritized vulnerability.” That softness became a shared ethic, an atmosphere of welcome in every direction.

“Softness is ultimate acceptance,” Osorio writes. “It’s lush, warm, and welcoming.”

Their art does not beg to be understood—it invites you to witness. The specificity of self becomes a portal to the universal: a reminder that there is no collective without the personal, and no revolution without vulnerability.

Years ago, during a late-night conversation with their close friend Dr. Marcus Anthony Brock, Osorio had a realization that reshaped their relationship to legacy: “I am not more important than the work. My human vessel has an expiration date. My ideas—my paintings—do not.” That perspective freed them. Sharing their story became not just a personal act, but a political one: an offering of truth to future ancestors.

Nuzzo, too, sees curation as a spiritual practice—not a performance of mastery, but an act of co-presence and devotion. “When humans congregate,” she says, “spirit always manifests.” Together, Osorio and Nuzzo tend to art as altar, legacy as offering, and softness as strategy—for survival, for connection, and for the world we’re still learning how to make.

“Ese Es Casa” by Devin Osorio

Curating Kinship, Holding Complexity

For Nuzzo, Tomorrow’s Ancestors marks a turning point in her curatorial path. A graduate student at Columbia and founder of Cereus Art, she describes her shift away from the commercial art world as both personal and political.

“If fascism has used art as a weapon, capitalist liberalism has used it as surveillance,” she writes. “I wanted to reclaim creativity not as a privileged commodity, but as a radical force of connection.”

Her academic grounding—from Judith Butler’s ethics of vulnerability to Joseph Beuys’ theory of social sculpture—informs a methodology that privileges process over product, relationship over prestige. Curating, for Nuzzo, is a form of ecosystem-building.

She and Osorio liken their programming to cooking: choosing collaborators like ingredients, trusting the recipe will reveal itself in the doing. What emerged was a fiercely intergenerational, interspiritual, and interdependent space of belonging.

That care extended to how the curatorial role itself was held. “There are no observers—only participants,” Nuzzo reflects. “Curators should consider themselves a part of the projects they manifest, not isolated makers above it. It looks like listening more than you speak, but never a dereliction of our duty to contribute.”

Especially as a white curator working alongside communities she does not personally belong to, this meant leading with humility, context, and critical presence.

“You will never—can never—fully know. But that doesn’t absolve you from responsibility. Our limitations do not mean we should not call ourselves in to participate and elevate others’ creative and community expressions when we have the opportunity to do so.”

In that way, Tomorrow’s Ancestors became a practice in the decentering of whiteness, of curatorial ego, of institutional authority. And, as Nuzzo reminds us, this work is collective.

“Whiteness is violent towards people of the global majority and white people, just like patriarchy harms men. Dismantling it is shared labor.”

“Engaño Desconocido” By Devin Osorio

Becoming Tomorrow’s Ancestors

To become an ancestor is not to pass away, but to live with intention now. Tomorrow’s Ancestors invited every participant—artist, guest, collaborator to consider their responsibility to one another, and to the not-yet-born. It asked how our narratives ripple outward, and how memory can be a communal offering.

Osorio writes, “I’m not longing for the past I lived, but for the past I deserved.” That longing animates their work—not as nostalgia, but as world-making. Their snow-globe metaphor says it best:

“If the viewer knows to pick it up and shake it, all of the glitter and magic—the intentions, incantations, and invitations—begin to swirl.”

The same could be said for Tomorrow’s Ancestors as a whole. It shimmered because it was not fixed. It shimmered because it was tender, mythic, and fiercely self-knowing.

A house became a portal. A meal became a ritual. A gathering became a spell. And in that, something ancestral took root—not in bloodlines, but in shared breath.

Nuzzo said something I cannot stop thinking about: We want community to echo forward.

And what a stunning refusal that is—against forgetting, against flattening, against fascism. A future shaped not by spectacle, but by softness. A future that remembers.